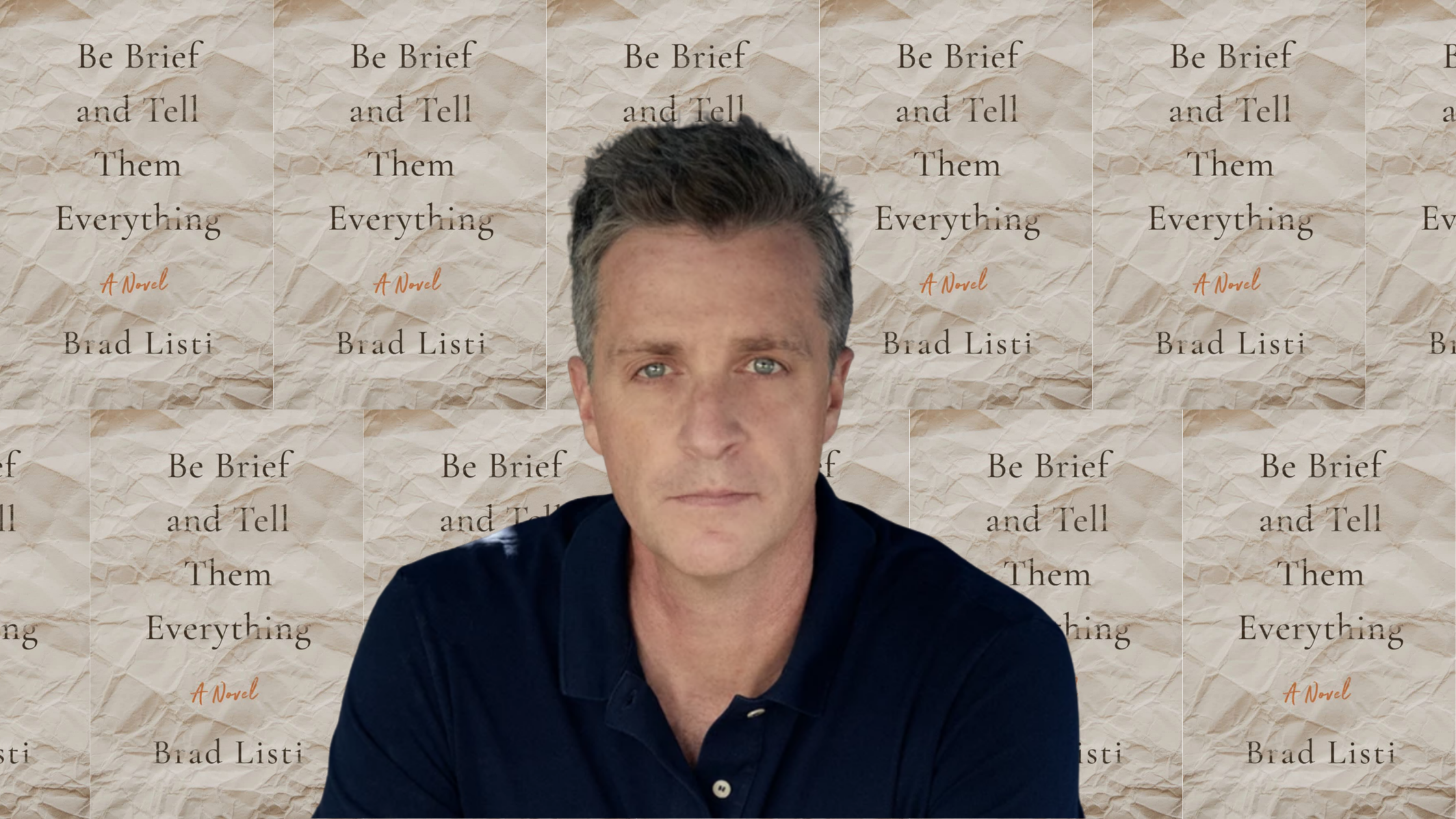

Brad Listi: On Writing Autofiction, Working Through Failure, Quitting Twitter, and His New Novel, "Be Brief and Tell Them Everything"

I first discovered The Otherppl podcast about 4 years ago, around the same time I started Write or Die Tribe. I was immediately drawn to the format, the more natural and casual tone of the conversations with writers, the musings of host Brad Listi before the start of each episode.

Listi’s latest novel, Be Brief and Tell Them Everything is a work of autofiction, set in Los Angeles. With sharp prose, tenderly rendered, and darkly laugh out loud moments, Listi explores fatherhood, grief, creative frustrations, psychedelics, art, parenting, and the trials of contemporary life. I wasn’t able to put down this delightful work that questions what does this all mean, what are we here for?

Brad and I spoke via Zoom about writing autofiction, failure as part of the writer’s job, social media and quitting Twitter, why we write, and what makes a good book.

Kailey Brennan DelloRusso: You kind of kick us off with saying that this book “started out as a novel and then it became a different novel and... then it was an essay collection and it was nothing for a while and then it was a memoir and then it became a novel again and now it’s whatever this is.” I love this because typically everything has to be a genre, has to be packaged in a way that people can categorize it and sell it and I think that can hinder us as writers. How did you get okay with having this book be “whatever it is?”

Brad Listi: I mean, it says a novel on the cover. In the end, it's a work of fiction, but it's also a work of fiction that's very much about creative exasperation. It's also auto-fiction, so it's pretty close to the bone. I think it's not uncommon actually for books to go through iterations like this. I don't know if it always jumps around from category to category or genre to genre but I think that happens more than people might think. Especially like a work of autofiction can easily find itself leaning more toward memoir in certain phases. And then you might revert back. I think with books that are elusive or difficult to nail down, a writer will often experiment just to try to stay busy. That was the case for me. It was like, well, this doesn't seem to be working. Let me try this. And then I would go down that rabbit hole for a while until I realized that it too was a lost cause. And then eventually through trial and error, you get to a place where the thing works, hopefully, and that was the case for me. It was just slow going and a very long haul.

KBD: Yeah. So I’ll be honest, I haven’t read a ton of autofiction. But as someone who listens to your show, I know some things about you. So as I was reading I was like okay is this Brad-Brad or Brad the character? So how were you thinking of it as autofiction?

BL: Well, it's mostly me. I mean, it's very personal and I'm intentionally being vulnerable on the page, but it's also very much fiction and there's a lot of stuff in the book that's made up. And that is a matter of convenience for me. It's also a matter of having a pretty spotty memory. It's a matter of trying to take a book that has lots to do with tedium, like creative exasperation and grief and trauma, and trying to put that into a narrative that is workable for a reader. In order to do that, I found that having the freedom to fictionalize helped quite a bit because I wasn't bound by facts, which I couldn't really remember anyway. It just became the obvious path for me and maybe the most natural path for me.

I like autofiction as a reader. That's not all that I like. I like everything if it works. Like if you can imagine my particular preferences or predisposition and you think of me doing the podcast and wanting to interview authors in addition to reading their books, I always trying to figure out what's going on with the person who made the art. Maybe this makes me strange. Maybe this means I'm missing the point. I don't think so. And so with autofiction, it's kind of lovely because there's less art between the author and the reader. There's fewer machinations and it feels personal and urgent and a little bit risky. And I always appreciate that in books when it's rendered well.

KBD: I really enjoyed how candid you were about the struggle to write a novel. You speak about certain topics or themes you explored but how you felt like it just wasn’t coming together. I want more of this in the writing world because we only see the finished product and can’t help, sometimes, comparing our first drafts of something to an already published work (laughs)

I was curious if you felt a little uncomfortable sharing that part of your writing life, especially compared to all the writers you speak to on your show where you are always sort of talking about accomplishments. Could you talk a little bit about that?

BL: I wasn't that self-conscious about it. If I'm blessed with anything it's that I'm not a competitive person. I mean maybe there's some of that in me. I think there's some of that in us all, but it's really not excessive. I don't have any problems celebrating the successes of others. The successes that people have who guest on my show don't bother me. I think part of it is that I know all too well, how much failure goes into any success. I know too much about the writing life to believe in any kind of like fairytale story of what's happening. And I also think that I eventually came to terms with the fact that I was trying to write a very difficult book. You know, I think that the stuff that I was trying to deal with personally and creatively is just inherently tough. It’s tough at the level of creativity. It's tough at the level of emotional and psychological processing. So I guess I was able to forgive myself a little bit on that front, especially now that I kind of figured it out or got it to a place where it worked.

But I think that one place that I'm particularly fascinated is with the notion of good ideas that just aren't right for me. Like I think some of the failed iterations of the book that I describe in the novel, and some of them are really good ideas. Like I think a novel about a guy who tries to sell his kidney because he's broke and in credit card debt, is actually a good idea. When I tell most people that premise, they sort of spark to it. But I couldn't write it. And you know, I'm interested in that. Like, wow, you can have a really great idea, but it might not be the book that you are designed to write, you know? And I think we can only write the books that we have to write or that we're really wired to write. And for me so far anyway, autofiction and working from the inside out tend to be my mode.

KBD: I understand that. I’ve been rewriting and rewriting the first 50 pages of my novel for so long. I knew it wasn’t going to be a fairytale but I didn’t really understand what other writers go through until I started to tackle it myself.

BL: Listen, it's hard to write a book. Novel, memoir, biography, essay collection. I don't care what it is. Writing any long form piece of literature is one of the harder things that a person can do. And I say this not only from my own experience, but having talked with hundreds of writers over the years on my show. I also say it as a passive observer. Somebody who's reading interviews in magazines or listening to interviews on other podcasts. I will often hear and sort of smile when people who work in other media, you know, like a comedian or an actor or somebody who's tried their hand at writing a memoir, talking about what a pain in the ass it is to write a book. And I'm like, yes! Yes, it is! I've also done some screenwriting and will sometimes have friendly debates with friends of mine in Los Angeles, about how much harder it is to write a book than a screenplay. Writing a screenplay or writing for television by comparison, to me anyway, is easy. That's not to say that it's easy to write a good one or it's easy to get one sold or to jump through all the hoops that one has to jump through to navigate Hollywood. That part of it is hard. The writing itself is actually not that terribly hard once you've failed at writing a novel for a decade (laughs).

You can get an episode of a TV show written in a week. But writing a book is a difficult challenge. And I think one of the things that is both disheartening and heartening at the same time is that failure. And especially large scale failure, meaning entire bad books of which I wrote many on the way to this one. 500, 1000 1500 pages of garbage. Even for people who are incredibly accomplished and who have won a ton of major awards. I think the sooner that we, and I definitely include myself in this, can come to terms with this the better off we'll be.

It’s just the job. The failure is the job, the search is the job. Having the patience to write an entire bad novel, and then say, well, that didn't work, I’m gonna start over from scratch with maybe like a few lines or paragraphs or pages from this disaster that will set me on my way. And having the emotional wherewithal to not crumble when that happens. It's not simple, you know? I think for most people it's like, this is hell, I'm getting outta here. I don't think most people want anything to do with it once they've actually gotten into the weeds. And so I think what happens is either a person writes a bad book because they lack the patience to finish and to condense and to do the hard work on behalf of the reader that would seem to be the responsibility of the writer. Or they just quit or they get a ghostwriter, which might be the smartest move of all (laughs).

KDB: It’s this thing I want to conquer, you know?

BL: I hear you. That's another thing that I think will serve you and will serve any writer well- it might be a common thread among writers- is that we're the crazy people who can't quit. I tried to quit. There were many times when I was like, you know what? I don't have to do this to myself. I don't have to put myself through this really grueling exercise in careful attention, which is definitely the case when you're writing any kind of grief or trauma narrative or a narrative that even involves those things. That especially. Really this book is a lot about the hardest parts of my life and the most embarrassing and vulnerable parts of me (laughs).

I’ve said this in other interviews that I've done and it holds true. I gave myself a challenge, to write a book as if I were already dead. What would I say if I were already dead, or if I were on death’s door? Just as a creative exercise and a kind of challenge to myself. And then also I think I was in this headspace where I was like, if you're gonna put yourself through this, what do you really have to say? Like, what matters to you? What are you afraid of? What hurts? What can you possibly say that could be of use to other people? None of this is gonna matter probably all that much in the grand scheme of things. We’re all gonna turn to dust eventually, right? All of this is gonna go away. So it's just trying to see things through that lens and to write with some urgency and to be as fearless as possible and to really pay close and careful and slow attention to the hard parts.

KBD: Was the publishing process long? Did you have any trouble finding a home for this book?

BL: It was fairly long. I don't think this is necessarily one of these books that has traditional markers. Like you say, it's odd in its market placement. Is it autofiction? Is it a memoir? There's a lot of that kind of confusion and it deals with some tough stuff. I think I have a strange sense of humor at times. But then at the same time, I've been hearing lots of great things. So I don't think it's easy to predict how the reading public is gonna receive a work, but I can understand from a pure business perspective why it took the right publisher and the right sensibility. It’s little bit quirky though I hate with a passion that term, because it's always been applied to me. ‘You know, we really like you, but you're just a little quirky’. It just means they don't know how to sell it and make lots of money at it in a really easy and direct way. I don't begrudge them this, this is the business of bookselling. You're looking for books that you feel will have a wide audience, but that also succeed, as literature or whatever.

I think literary fiction in general is a space where a lot of the work that is made, much of it of high quality, just doesn't meet those markers, you know? And so it's a real guessing game and they get it wrong more than they get it right. It’s a gamble always in either direction. But as I always tell people on my show, or I always tell writers when I'm talking to them about this stuff, it really only takes one. You need a publisher who sees the value in the work and understands it and gets your sensibility in what you're going for. And hopefully, they can also add something to the process and help you realize the best version of the book. But as long as you find that and the book gets into print and readers can find it fairly easily and get their hands on it, that's it. That's all you need.

KBD: Your commentary about social media in the book was so funny and so true. I know you made the decision to get off Twitter but also grappled with what that would mean for you as a writer and podcaster. You were kind of afraid would you disappear without it. I was totally on board with you.

BL: And by the way, how funny has it been since Elon Musk's impending acquisition of Twitter has been announced to watch all the mental gymnastics of people on Twitter who are trying to pay credence to their moral and ethical sensibilities while also being terribly addicted to Twitter and like needing the dopamine hit of the retweets and likes and all the love on social. There's a cynic in me that's like, none of you are gonna quit. (laughs) And even the people who make a big show of quitting, they're gonna come back. And you know, I don't say that with pleasure necessarily. In my fantasies, everyone would just quit at the same time on the same day and it would just go away and he would have to eat 45 billion dollars. It would be the most beautiful justice like ever realized on this earth.

I think for me personally, it just became too much. I was too addicted. I couldn't personally handle it in the way that I think a lot of people can. And I don't want to project my particular experience onto everybody's experience. I know we are all special snowflakes with our Twitter, but I also think a lot of us are just addicted. I had to break the addiction to finish this book. It's not an accident that the finishing of this book happened after I quit Twitter. It is not an accident that my reading of books skyrocketed after I quit Twitter.

But I should also confess that I read Twitter. I don't want to be too holier than thou because I am constantly reading Twitter. For me, Twitter is the internet. I don't surf the web from like website to website. I go to Twitter and scan through and read lists. That's just how I aggregate the internet basically. And that's not necessarily healthy. I'm on it too much, even on those terms, but taking the onus off of myself to be an unpaid contributor to Twitter and creating content for them and sharing all that data. I mean, I have my data settings turned off as much as one can turn them off on Twitter, but just not being an unpaid contributor makes it markedly healthier for me. I feel better about it that I can live with this compromise for now though. Ultimately I would love to be done with all of it and just like live in the countryside and read books and be smug.

KBD: Ugh. Yes.

As a podcaster, who has interviewed hundreds of writers, how was this changed you as a writer and as a reader? Are there different genres you discovered, for example, that you didn’t know you liked before?

BL: I think the podcast has sensibility broadened my taste. I'm open to anything. I really and truly don't have rules for what's good and what's bad. I might have some preferences. I said that I often liked autofiction, but not always. I think we can sometimes get into these moods where we think we know ourselves or we think we know what's good. Art, I think, succeeds on its own terms. You can watch a Pixar movie and it's a children's movie, but if it succeeds on its own terms, you can enjoy it. Even if you're not somebody who gravitates toward kids' storytelling. You find that as a parent really easily once you're stuck watching Shrek or whatever on the weekend. I think this is the case in books. A thriller succeeds on its own merits. A work of autofiction succeeds or not based on how well the author executes for you.

I love crime fiction. I love desert noir. I love essay collections. I love humor. I like poetry. I like it all if it is working for me. And whether or not it works for me, depends on a lot of factors. It depends on how much work the author has done on the page. I can sometimes feel frustrated when I feel like a book is undercooked. I feel like they should have spent more time. I think a lot of readers maybe feel that way. Sometimes it might be overcooked - who knows that's a little bit harder to define. But you know, when a book works for you, it works for you. And I think that the podcast has taught me that I can enjoy just about anything and that I should be open minded and not be hardheaded about what I think real art is.

The other thing that the podcast has taught me is that there's just an absolute embarrassment of riches in literature. There are so many great books out there, most of which nobody has ever heard of before. Some of which literally nobody but the author has heard of. They're just sitting in a drawer somewhere and I bet they're masterpieces and this sort of, I think, contradicts maybe prevailing wisdom. That seems to say that masterpieces are rare and the cream rises to the top and some people are just better. That Toni Morrison is just great, which she is. But so are a lot of novelists that nobody has ever heard of that I would strenuously argue and pound the table for. I think that is a lot of what keeps me going doing my show, the kind of panic I feel when I read a book that I think is just superb, just beautiful literature, rendered perfectly on the page, in my eye. And I think about it selling 476 copies or whatever. That both makes me feel a sense of panic on behalf of the author, panic as a reader, and a sense of like outrage, you know? I think that's a lot of where my advocacy comes from is trying to bump this particular kind of art a little bit back toward the center of the cultural conversation.

Brad Listi was born in Milwaukee. He is the author of the novel Be Brief and Tell Them Everything (Ig Publishing / May 2022). His other books include the novel Attention. Deficit. Disorder., an LA Times bestseller, and Board, a work of nonfiction collage, co-authored with Justin Benton. He is the founding editor of The Nervous Breakdown, an online literary magazine, and in 2011 he launched the Otherppl podcast, which features in-depth interviews with today's leading writers. He lives in Los Angeles.