The Poetry Report from Pathology

I would never offer a patient a poem about their leukemia. But sometimes I write them.

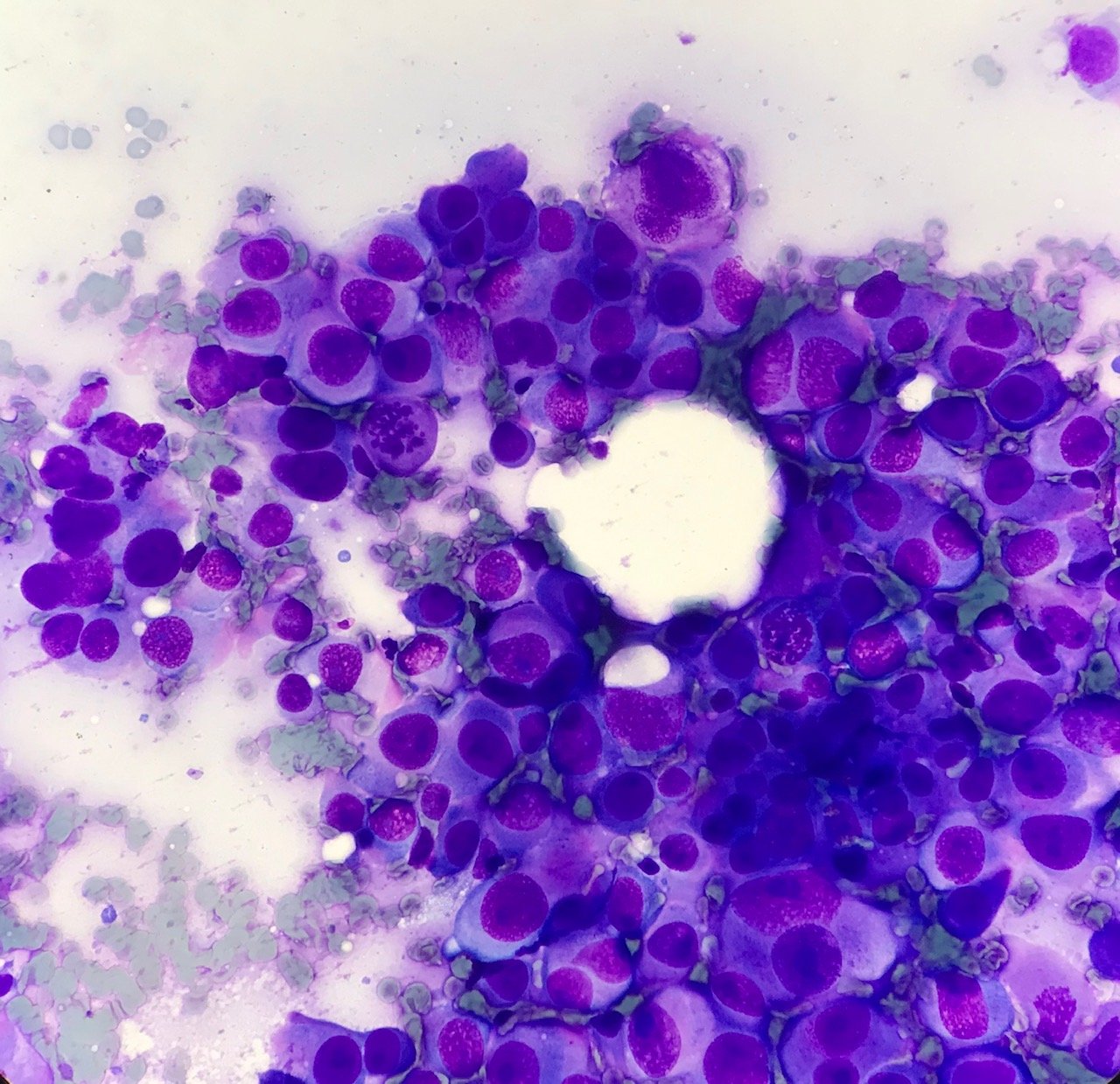

Acute Leuk

His cells crumpled blue

tissue paper collisions

bring about the end

Every day in my work I write about pathology in my reports. I list the type of tissue that I am examining, the procedure that the surgeon performed and I assign a name to what has gone awry in the patient, also known as a diagnosis. The report is a missive that goes out to the world, released from the electronic medical record directly into the patient’s chart. It is a private communication about the patient to the doctor. The vocabulary is rich, idiosyncratic and highly specific. Every word matters — just like crafting a poem.

BKA: Fem Pop Fem Flop Fem Chop*

A phantom to plumb

your heavy limb cold, filled with

soft suppuration.

Pathology is: the science of the causes and effects of diseases, especially the branch of medicine that deals with the laboratory examination of samples of body tissue for diagnostic or forensic purposes. Pathology occurs behind the microscope and in hospital basements, the hidden specialty undergirding all of medicine. It isn’t usually written for the average person to read.

Writing about pathology occurs in a very structured, formulaic manner. When I was a resident in training at an academic medical center, I wrote about pathology in research papers. I examined how and when cancer arises within a benign proliferation. I cataloged the occurrences of a particular growth pattern of a tumor. I described how certain deposits look and what they are made of.

These papers were shared with other pathologists to help them look more closely at the tissues on their cutting boards and under their microscopes, to notice the correct things and ignore the distractions. Notice-taking is the core of pathology and case reports are tools in the honing process that is our ongoing education in anatomic pathology. Research and experience —in pathology and writing— are part of how we learn what matters and what doesn’t.

Cross sections

Like a puckered kiss

tubes squeeze shut under the light-

no space left unprobed.

Lately I’ve been writing about pathology for myself, to better understand how my work is so intimately wrapped up in the patient’s experience. I’ve started writing about it in my poems.

The background knowledge needed to understand pathology is overwhelming. Some medical students, their basic pathology coursework fresh in their minds, are interested in my writing about pathology. But most of them are far too busy studying. I wrote this next haiku with them in mind because all medical students know about the strange proliferations that arise in the ovary, but they aren’t as yet familiar with the bloody tissue that means a death sentence.

Evaluating a complex ovarian mass

Crumbled white tumor

Everyone knows about teeth

Not this catastrophe

There is a lot of overlap between Pathology and visual art, so much so that I’ve considered some of my writings about pathology almost as Ekphrastic poems. Superficially, many specimen slides when photographed as a still image are beautiful. And, like Art, Pathology offers a visual education in how to look. My poems are ekphrastic exercises if we consider the body —in health and disease— as a work of art

In Art History, you learn to describe the painting, artist, year and then contextualize the meaning and the visual effect. In Pathology we learn the organ, tissue, inflammation, neoplasia …and everything else. Your eye becomes trained through repetition to notice the important features. It might be considered similar to art appreciation — if the painting itself held the key to whether you live or die.

We even use paints in our gross examination to orient tissues.

I lay out your breast in slices, pancake-sized

—the kind they call silver dollars on the children’s menu —

greasy slabs painted in 6 different colors

like a compass rose:

Anterior orange, Posterior black

Medial green, Lateral yellow

Superior blue, Inferior red.

Notice taking is built into both Pathology and poetry. Notice the unique features, describe the specimen or subject with detail and all five senses. Convey the nuance in specific words and avoid generalizations.

Colon Resection

Burnt and stapled ends

lurid volcano within

erupts at first light.

Poems rely on metaphors and we in Pathology are always trying to explain things with metaphors — most infamously through food. Tumors can be pea-sized or the shape and heft of a cantaloupe. Our abdominal fat, studded with tumor deposits, forms a cake. The inflamed and shaggy heart lining looks like bread and butter. The cut surface of some tumors look like cabbage or potatoes. Lymphoma looks like the firm white flesh of fish.

There is some movement to discourage the use of metaphor when talking about pathology —too familiar, too unprofessional, too disgusting. But the persistence of these descriptions speak to me of the power of metaphor, and ultimately the power of poetry. It can be the fastest way to communicate and share an image.

Inside

At the smorgasbord:

chocolate cysts, fatty folds.

No one goes hungry.

Pathologists are not maudlin and we are not disgusted by the physical realities of life. The subjects of pathology —life, death, and how that happens— are the same story addressed by many poets. Gregory Orr, who writes about the power of poetry in his book of analysis Poetry as Survival, has written excruciatingly beautiful poems about death and remorse that resonate with me, the pathologist observer.

The Journey.

Each night, I knelt on a marble slab

and scrubbed at the blood.

I scrubbed for years and still it was there.

But tonight the bones in my feet

begin to burn. I stand up

and start walking, and the slab

appears under my feet with each step,

a white road only as long as your body.

-An excerpt from Gathering the Bones Together

Poems, like pathology reports, can reveal a truth; no matter how large and imposing we try to become, encased in insulation against the modern world, inside us the smallest of forces can bring us down. Indeed they always have.

Mary Oliver, my favorite poet, is known for her rendering of nature in evocative emotional language. But her poems are not catalogs.

“It has frequently been remarked, about my own writings, that I emphasize the notion of attention. This began simply enough: to see that the way the flicker flies is greatly different from the way the swallow plays in the golden air of summer. It was my pleasure to notice such things, it was a good first step. But later, watching M. when she was taking photographs, and watching her in the darkroom, and no less watching the intensity and openness with which she dealt with friends, and strangers too, taught me what real attention is about. Attention without feeling, I began to learn, is only a report. An openness — an empathy — was necessary if the attention was to matter. “

Pathology relies on attention without feeling. I am expected to generate a meaningful catalog of observations and then translate my attention into the report. But the simple fact is that I, behind the microscope, am not insensible to the effect of my stubborn immutable words. I know some words and names for disease are freighted with meaning and upheaval. Abscess. Cancer. Dysplasia. Invasion. Metastasis. In my pathology reports, you don’t hear the full scope of my attention.

Fly Away Home

This thin cap of scalp,

nest chock full with birds of prey,

ready to escape.

Paying attention is how I care, and in the moment it is satisfying enough to accurately identify the pathology and generate the report. But over decades of work and practice I have come to realize my attention needs feeling to matter to me. I need to reconnect with my own empathy to matter. That’s where poetry comes in.

To craft a poem feels immensely difficult, which is a bit like pathology. Unlike pathology, poems are about feeling, about the space inside where the images from the world meet up with images from my mind. In my work, I look through a microscope and identify a tumor. It grows a name, one I then tell you.

___

*

BKA = below the knee amputation

Fem Pop, Fem Flop, Fem Chop. A bitter medical aphorism of vascular surgery; to save a leg without proper circulation, a femoral-popliteal artery bypass is performed. Soon, it flops, or fails, leading to the definitive treatment - amputation.

Jena Martin is a writer and pathologist, currently at work on her literary thriller about two women grappling with the effects of the recovered memory movement. Her writing reflects the pathological, celebrating the beauty that can be found in the grotesque